COX VOX: Weaving First Nations Cultural Practices with Personal Storytelling with Andrew Parish

As it comes to a close next month, we reflect on the Australian Pavilion of one of the most renowned architectural events, the Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia 2025.

For the first time, it was led entirely by a First Nations design team, including Creative Directors: Jack Gillmer-Lilley, Emily McDaniel, and Dr Michael Mossman. Their exhibition, HOME, is a participatory, multi-sensory space where First Nations making, storytelling, and yarning shape reflections on culturally safe spaces within institutional architectures. Visitors walk barefoot on sand, leave traces of ochre and clay, and interact with tactile artefacts called ‘Living Belongings’.

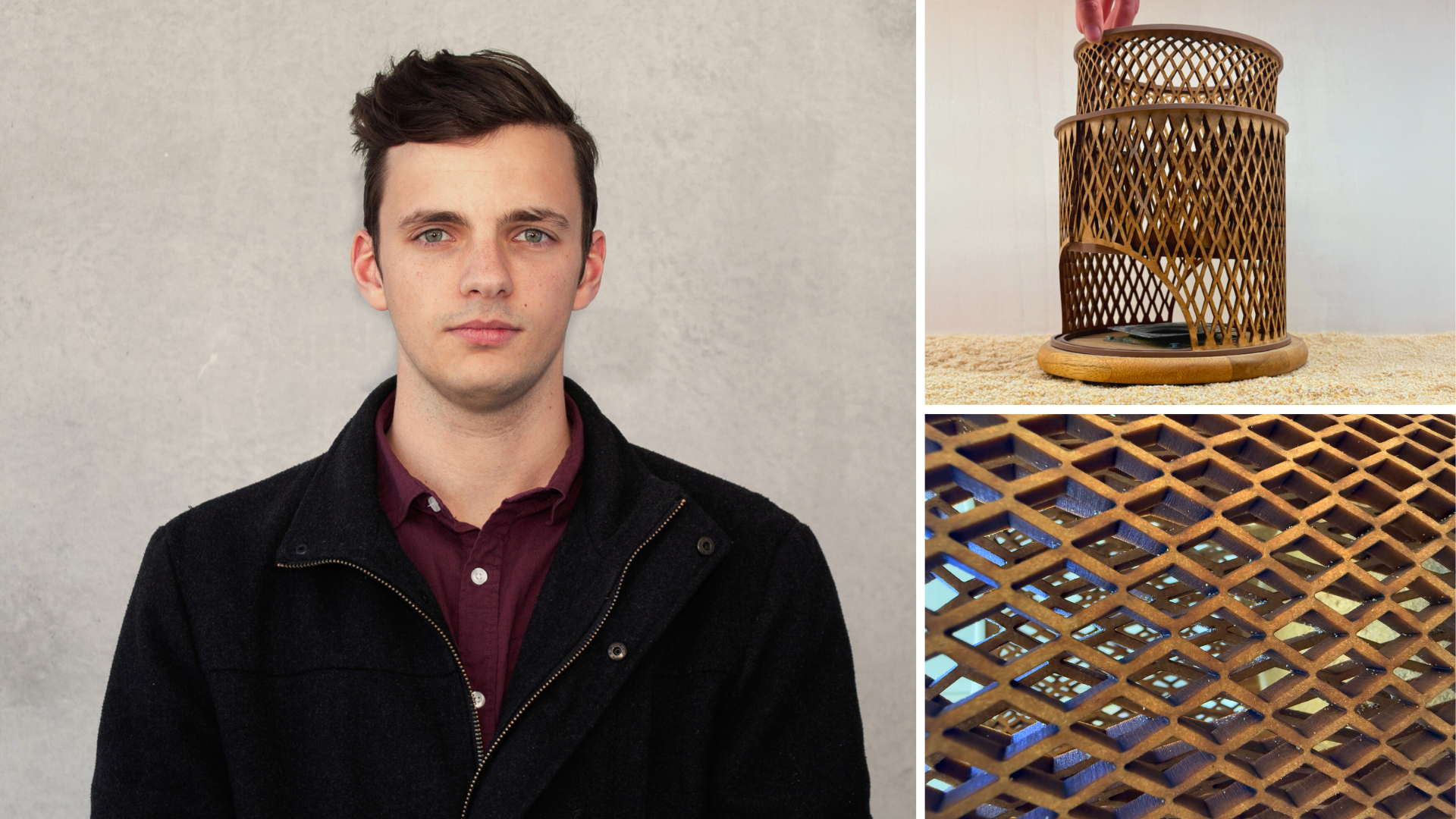

Among them is ‘Carved Through Experience’ by Andrew Parish, an Australian man from Yolngu Land (Nhulunbuy) in remote Arnhem land in the Northern Territory currently completing his Master of Architecture while working as a student in the COX Canberra studio. The creation of his piece was part of a three-week intensive workshop, where participants were invited to design a ‘living belonging’ – an object that expresses their personal and cultural reflections on home. Of the 125 students involved, Andrew’s design was one of just 20 chosen for the opening display in Venice.

We spoke with Andrew about his design process, how memory, movement, and cultural practice shaped his work, and what it means to have his personal artefact on display at a globally renowned exhibition that has since welcomed visitors from around the world.

Q: What was it like to be selected for the exhibition, and how did it feel to have our work shown on a global stage?

Pretty surreal I haven’t even left the country myself, and yet something I created is now displayed at one of the most significant architectural events in the world. Coming from Canberra where the universities are smaller, it felt even more meaningful to have something from here make it all the way to Venice.

Q: Can you describe the concept behind your piece and how it explores the idea of home?

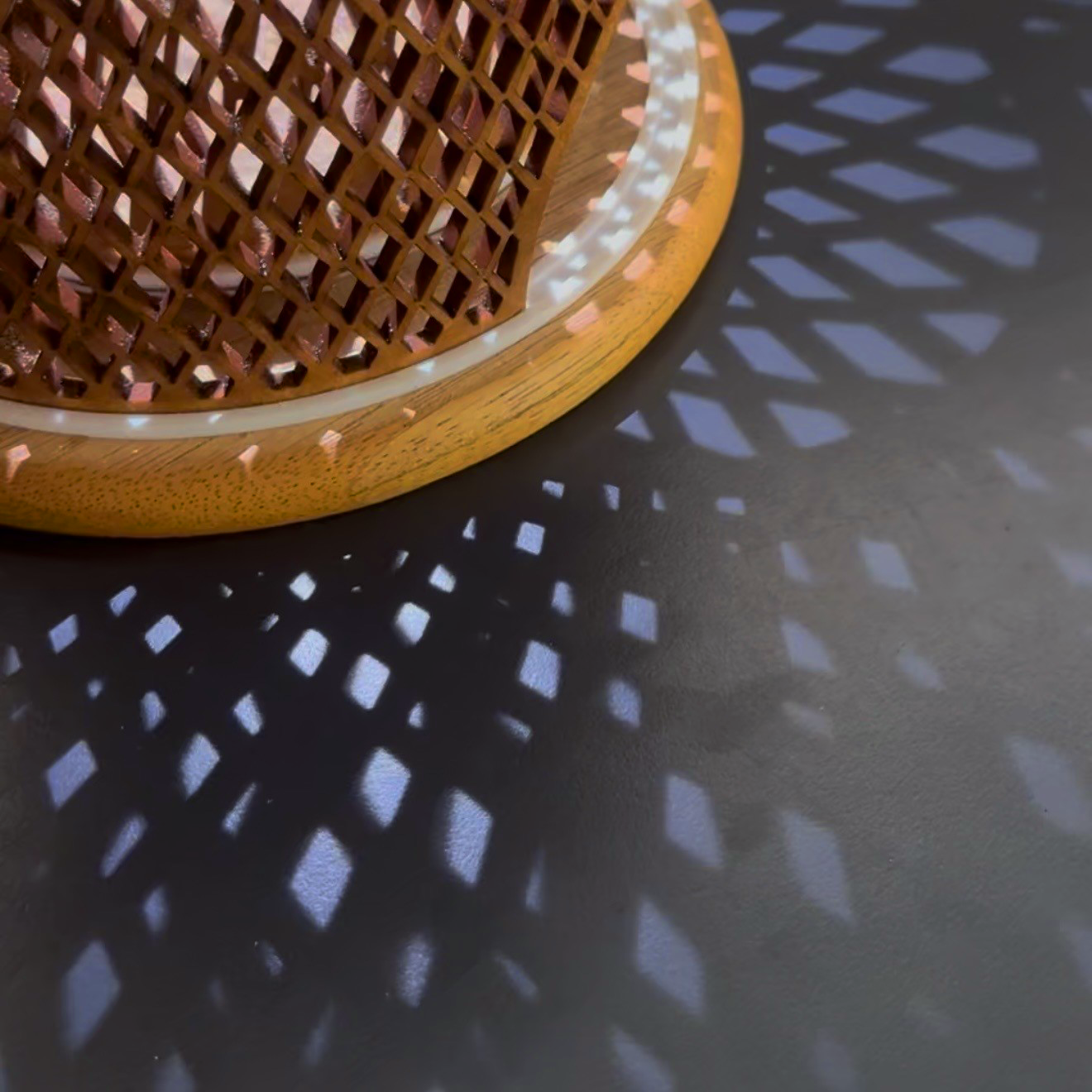

The sculpture reflects different elements and states of water. Each component connects to water either symbolically or through how it was made.

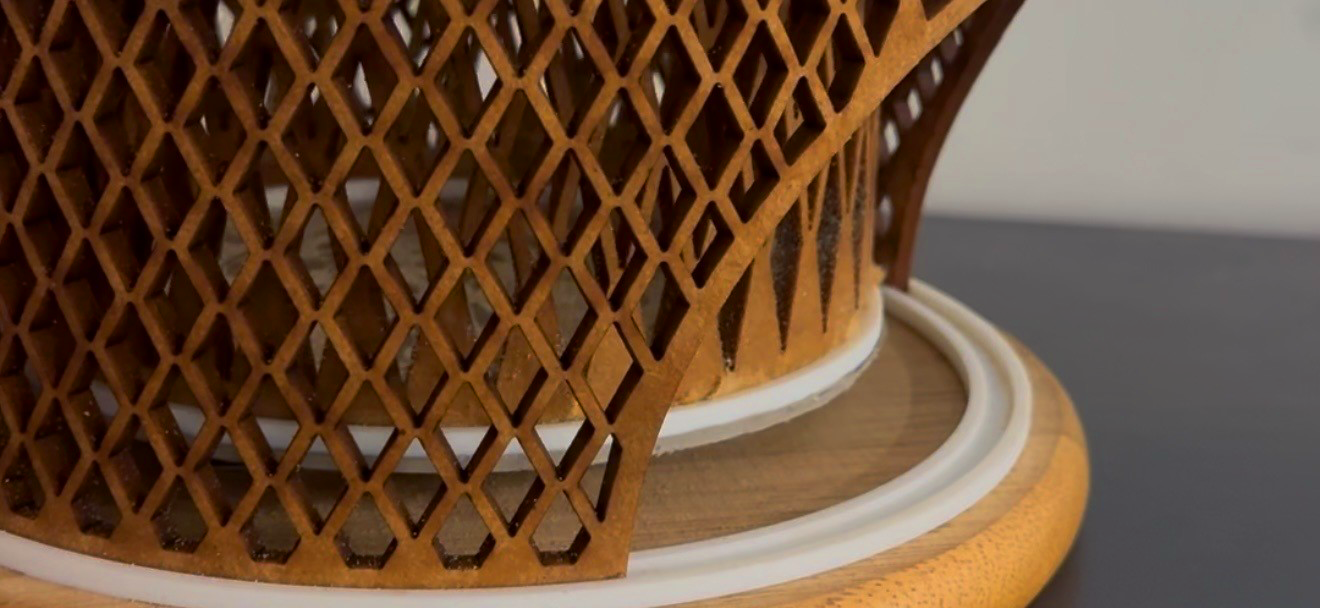

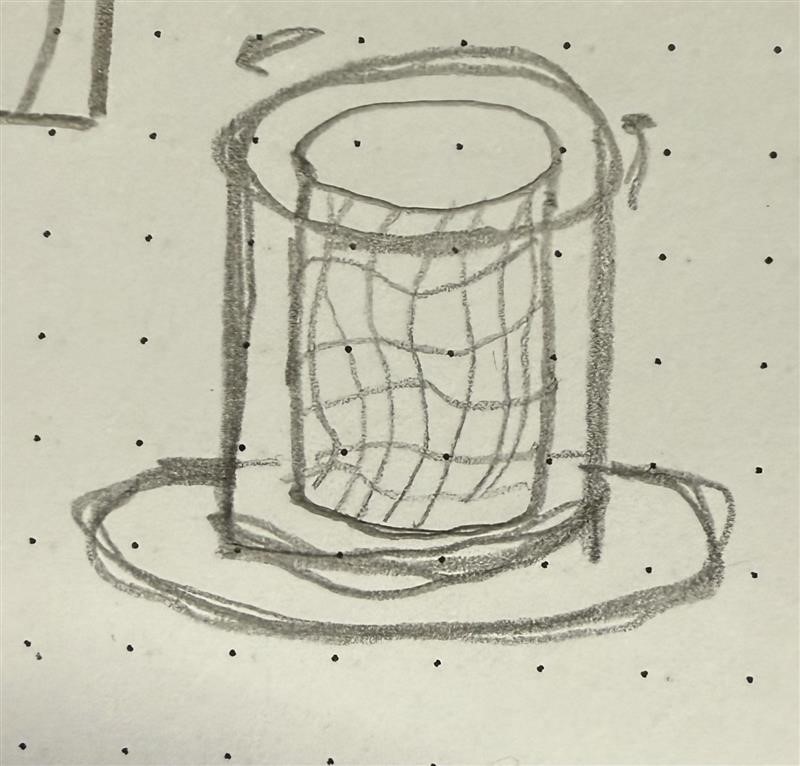

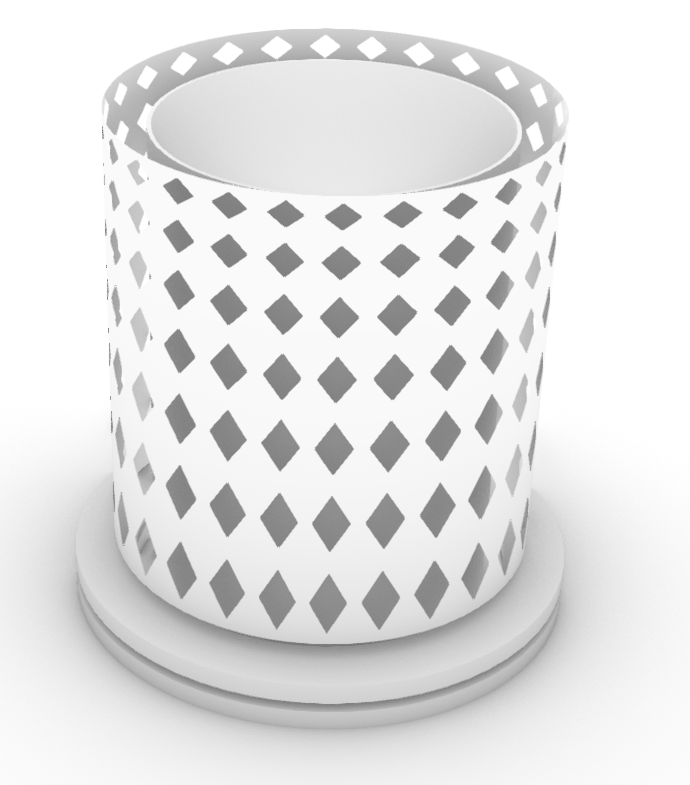

It’s made up of two cylinders: the outside is fixed whilst the inside can be manually spun. When rotated, the layered grid patterns create a moiré effect that mimics light filtering through rippling water. I’d initially planned for it to rotate automatically with a light source at the centre, but since it needed to withstand six months of public interaction with no maintenance, I simplified the design to be manual and durable.

The rail is filled with sand, so when spun, it creates a soft, rain-like sound. That sensory layering—sight, sound, touch—was a really important element to me. I wanted people to engage with more than just the visual.

The spinning also represents rainfall, and when still, it evokes drought. Water is universal, but in Australia, it’s also extreme. It can give life and take it away. That tension was central to the concept.

Q: What drew you to water as the central theme, and how did your upbringing shape that choice?

I grew up in the Northern Territory, as far north as you can go. Life up there revolves around water. There are Wet and Dry seasons, and weekends were spent camping, fishing, and swimming. But water also shaped what you couldn’t do. Jellyfish meant avoiding the ocean, and crocodiles meant steering clear of streams.

Everything was tied to water, and that’s why it resonates so deeply as my connection to home. Even now, the sound of rain on the roof or memories of cyclonic weather instantly takes me back without needing to physically be there.

Q: Your model is very sensory and interactive. Why was that kind of engagement important to you?

Interactivity was part of the brief, but I knew from the start I wanted people to physically engage with it – spin it, look at it from different angles, and watch the patterns shift. That sense of play invites interpretation.

Water is something we all know, but we experience it differently. The moiré effect, flexible timber, shifting shadows, and soft sand sounds all offer different entry points. It’s not about telling one story; it’s about inviting many.

Q: How did cultural practice and natural materials influence the design process?

The program was Indigenous-led, and we had to use at least 95% natural materials or create it using natural processes. That really pushed us to think differently.

For me, cultural practice meant expressing my relationship with Country through water. Others took different approaches, but there was a shared respect for meaning, materiality, and story.

Early explorations of ‘Carved Through Experience’ through renders and sketches

Q: How did working with students from around the country shape your experience of the program?

It was fascinating. Everyone had a different take on ‘home.’ One student based their piece on a plastic chair. They had grown up on a vineyard and the chair was used for everything: helping the elderly sit, as a step to reach things on a tree. It followed them everywhere.

That kind of storytelling made me appreciate how varied our experiences are. The range of perspectives created a genuinely collaborative and rich learning space.

Two works in particular stood out to me – Shan Shui (Prophecy) by Kien Situ, and Catalyst of Connection by Lily Pertyl.

From the dialogue of the materials, to the engaging sculptural forms that invites interaction, I thought these were particularly interesting through their unique ways of expressing and interpreting the idea of ‘home’.

Q: Did your role at COX influence how you approached this project?

Definitely. Working on the computational side at COX gave me the tools to experiment with layering, geometry, and fabrication techniques like laser cutting. I was able to iterate quickly and test ideas digitally before making them.

It helped me think practically about how to design something that was both durable and meaningful.

Q: What did you hope people take away from your work in Venice?

I hope they engaged with it through the senses first – the play of light, the sound of the sand, the motion in their hands. And then, maybe, they were able to reflect on their own relationship with water. Where did it show up in their lives? What did it mean to them?

Water is everywhere, but we each experience it differently. I wanted this work to feel alive and open, so everyone could bring their own meaning to it.