COX VOX: From Uncertainty to Purpose with Piper King

Emerging designers like Piper King exemplify how meaningful mentorship and real-world opportunities can shape a purposeful career in architecture. For Piper, what began as a hesitant step into the field soon evolved into a journey filled with twists, turns, and ‘meant-to-be moments.’

Piper first connected with COX through work experience in 2017, before officially joining as a Student Designer in 2021. Over the years, she has grown into a professional whose work reflects COX’s dedication to inclusive design and meaningful community impact. Her portfolio includes projects such as the Murarrie Recreation Reserve International Cycle Park, Screen Queensland Cairns, Cazalys Stadium Masterplan, Logan Village Community Facility, Carl Street Social Housing, Southport Social Housing, Townsville University Hospital Outpatient Clinic, and the Richmond Football Club Redevelopment.

From uncertain beginnings in high school to a thesis on First Nations engagement in social housing, Piper’s story is one of passion and purpose. In the following interview, she reflects on her journey, the lessons she’s learned, and her aspirations for the future.

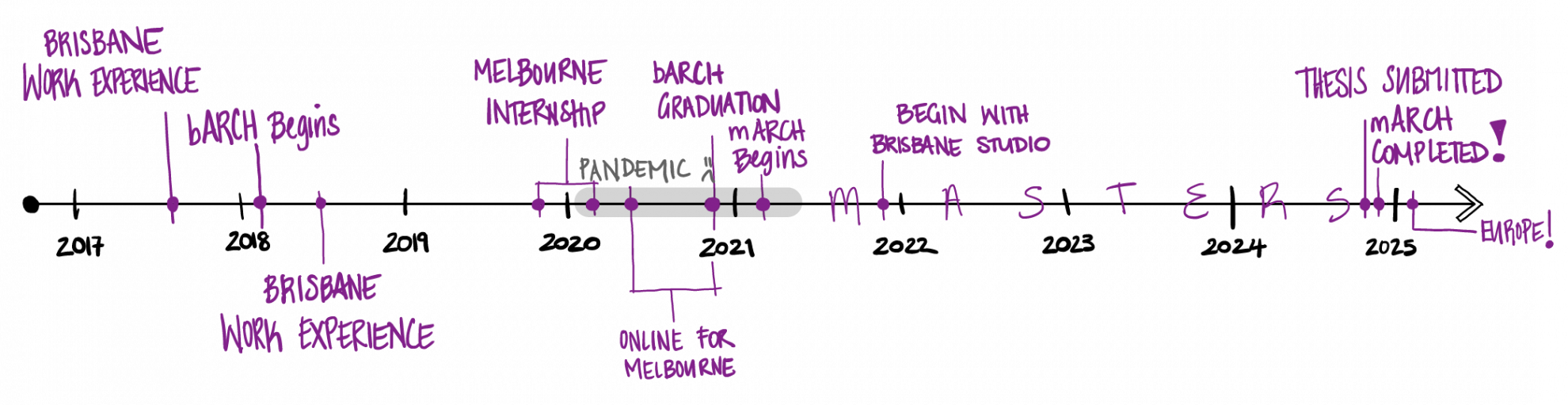

[Above] Piper’s timeline through her studies, work at COX, and beyond.

How did you first discover architecture, and why did you choose to pursue it?

Architecture wasn’t my first choice. By the second half of Grade 12, I still had no idea what I wanted to do. Graphics was my best subject, so my mum suggested I explore architecture. I wasn’t entirely convinced, but I gave it a go, and a work experience placement at COX completely changed my perspective.

That week opened my eyes to the profession. I realised architecture wasn’t about sitting in a dark room hunched over a computer, drafting endlessly. It was about people, place, and community. After that week, it clicked— I saw a career that satisfied all the things I’d been searching for. I could combine problem-solving, creativity, and a genuine care for people in a career that truly mattered. Architecture wasn’t just an option—it was the path. I applied to UQ’s Bachelor of Architectural Design program and was accepted, marking the beginning of my architectural journey.

[Above] Piper at her 2020 bachelor’s graduation ceremony at UQ.

Can you tell us about the journey that led you back to COX?

I first returned to the COX Brisbane studio for a week-long work experience during my first year of university. I then interned with the Melbourne studio’s sports architecture team during my second year. That experience sparked my passion for sports architecture, especially after seeing COX’s award-winning design for Optus Stadium.

Growing up in Queensland, sport was a big part of my life—my brothers played, my dad coached, and weekends were spent at games. By the time I finished high school, I’d tried seven different sports, with hockey becoming my social anchor during busy weeks. Sport taught me that community and shared experiences matter as much as the game itself—values I now bring into my architectural practice.

In 2020, I returned to Brisbane with plans to rejoin the COX studio, but the pandemic disrupted those plans. So for the next six months, I worked remotely for the Melbourne studio while completing my degree. When Melbourne’s lockdowns persisted, I explored other roles in a children’s psychology clinic and space planning at UQ’s Property and Facilities team before returning to COX’s Brisbane studio in late 2021. And I’ve been here ever since.

What was it like working while studying, and how did it shape your learning?

Balancing work and study was tough but rewarding. UQ encourages work experience, and although I didn’t follow the typical path, the practical exposure I gained in industry made me a stronger student.

Working at COX allowed me to contribute meaningfully to projects and learn from senior team members, which helped me hone my skills and build confidence. These experiences gave me a deeper understanding of how academic concepts apply to real-world projects. They also let me focus on the creative and human-centered aspects of design during my studies—reconciliation, community-driven projects, and design enjoyment.

Although it was challenging, balancing work and study was worth every late night and early sunrise. I encourage students to take at least six months to work in practice—it’s an invaluable experience.

[Above, Left] COX RAP event with team from Murrawin, led by Carol Vale, [Right] Piper in front of a second year Bachelors design assignment.

Can you tell us about your thesis and how it connects to your passion for First Nations engagement?

My thesis allowed me to dive deeper into my love for research and my passion for reconciliation in architecture—an interest I had even before starting my studies.

At UQ’s Open Day, I saw a student project for a First Nations Birthing Centre Clinic led by Kelly Green and Tim O’Rourke. It emphasised designing with empathy and culture, which struck a chord with me and showed me how architecture could be a tool for care and reconciliation.

This passion grew during my undergrad, particularly in a course led by First Nations architect and academic Carroll Go-Sam, which challenged me to think critically about how architecture supports community identity. Later, in my master’s program, a course with Paul Memmott and Tim O’Rourke focused on social housing and the importance of environmental psychology and health. Tim eventually became my thesis supervisor.

I was honoured to receive the UQ Master of Architecture Thesis Prize for this work, which explored the National Aboriginal Health Strategy Environmental Health Program (NAHS EHP), a housing initiative rooted in participatory design and self-determination policies.

My thesis explored the National Aboriginal Health Strategy Environmental Health Program (NAHS EHP), a housing initiative rooted in participatory design and self-determination policies. Through interviews with architects and program managers and by reviewing design reports, I identified four key themes—presumption, program, people, and process—that influenced the program’s success. These themes revealed how flexibility, genuine consultation, and a commitment to empowering communities can lead to architecture that helps address the significant gaps in quality, quantity, and suitability of housing available for First Nations communities, particularly within the right systems and environments.

What resonated most with me was the deeply human aspect of the work. The architects I interviewed emphasised humility and the importance of community learning. This reinforced my commitment to designing spaces that uplift and empower First Nations voices—a value that aligns deeply with COX’s approach to community-driven architecture.

[Above, Left] Piper submitting her thesis, [Right] Piper heading off to Europe!

What’s next?

I’ve now graduated, and it’s time for Europe! I’m spending two months exploring, reconnecting with old friends—one of whom I met during university and is now a lifelong friend. It feels like coming full circle. I’m looking forward to the adventure, the art, the architecture, and of course, the good food. And, most importantly, the free time!

After that, I hope to contribute to significant projects like the Olympics—an exciting way to merge my passions for architecture, community, and global impact as I start this next chapter of my career.