CB Alexander College – Tocal

Paterson, New South Wales

CB Alexander College, now known as Tocal College, was one of the earliest projects undertaken by COX. Its design is historically regarded as one of the first large-scale exemplar of the ‘Sydney School of Architecture.’

Designed for the Presbyterian Church of Australia in 1963 as a specialist agricultural school, it was the first major commission for Philip Cox and Ian McKay, establishing their design reputation for environmental sensitivity. They adopted the very core of what the Sydney School would come to represent, basing their design on a local ideology and not the modernist institutional architecture of the time.

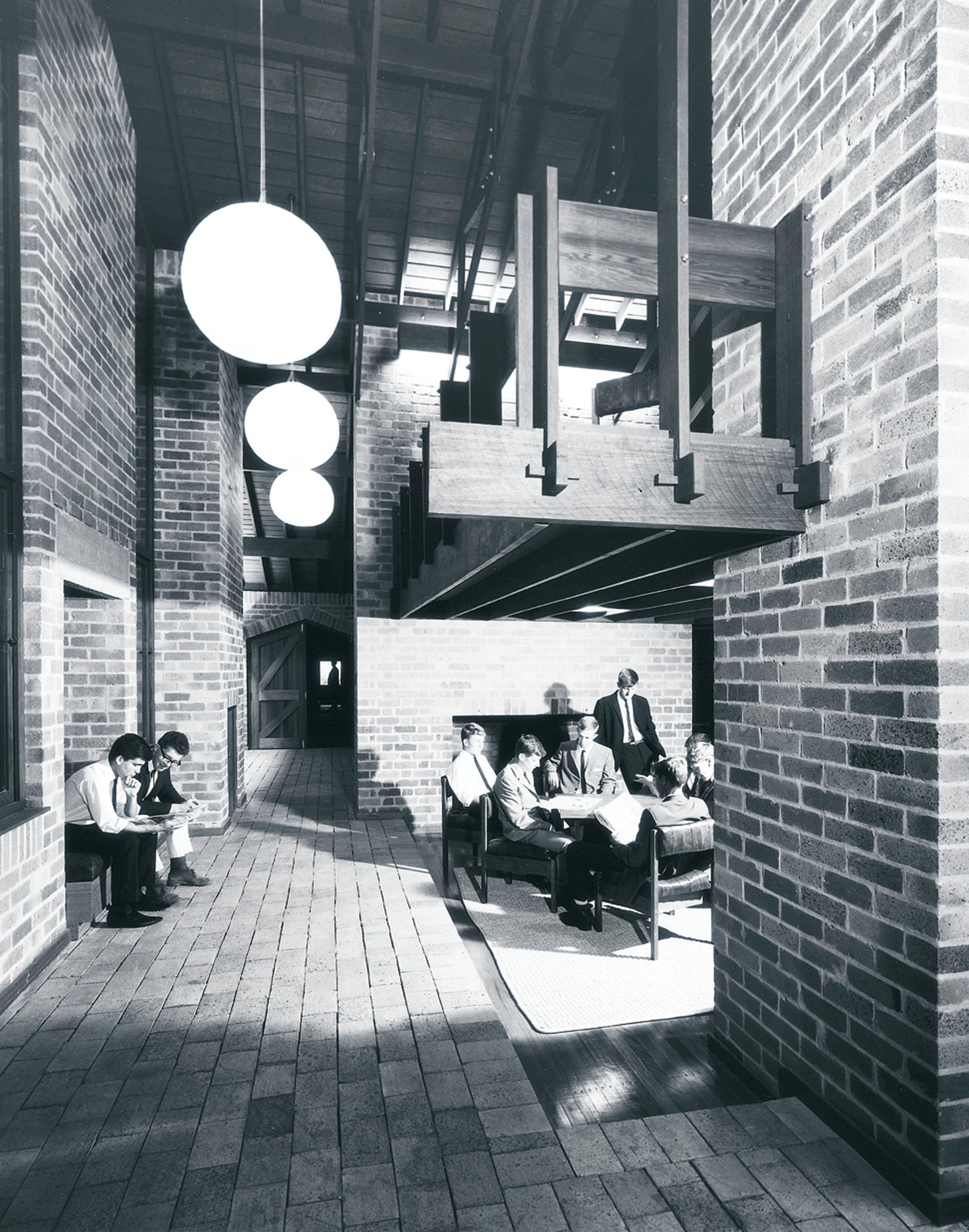

Reflecting the grander vernacular of silos and barns in the region, the college was alien to the structures that were being erected around it. The college helped form the key principles of the Sydney School, including loose extendable planning and integration within existing topography.

Alexander College, at the time of its build, housed 160 students and staff on a fully-operational farm. It provided single bed accommodation for 60 students, a common room, table tennis areas and reading rooms. The large assembly hall was used for theatre, badminton, basketball, gymnastics and other purposes. Staff accommodation included field offices, studies, master common room and a symposium room. The design also included piggeries, an intensive poultry system, bull pens and stables.

The overall college was planned, like many educational institutions, on a quadrangle – though one side was eliminated to allow a visual link to the homestead. This makes the campus a ‘u’ shape, facing towards the homestead with a series of courtyards as opposed to one centred courtyard. The student area sits to one side, with teaching and admin on the other.

The architects’ vision for the campus was that the college was to rise from the natural resources of the surrounding Hunter Valley – utilising local materials and local tradesmen. Alexander College was to mature and merge with the landscape – not disrupt it.

Landscaping was utilised to further reinforce this – with all plants utilised native to Australia. Lawns were mowed and maintained, but not watered – reflecting Australia’s four distinct seasons.

Impossible to ignore is the most dramatic of Alexander College’s buildings – the chapel. With a soaring spire and impressive roof form the chapel’s iconic peak caps a low angled brick base. Local tallow wood was used in this structure for its strength, the central pillar comprising one trunk which enables the spine to climb over 30 metres high. The dramatic form of the chapel’s spire is not only a focal point to the college, but a landmark that visually links the college complex with the homestead and surrounding farm estate.

The main hall pays homage to farm buildings – the Tocal Homestead designed by Edmund Blacket in 1867 to be exact. Blacket’s homestead used exposed structural timbers, king post trusses supported by poles and brackets shaped from tree roots and closely spaced battens supporting the roofing. The hall itself has roof trusses reminiscent of a mediaeval gothic church, supported by massive brackets, each made up of three pieces of ironbark mortised together.

The dining room sits on the eastern arm of the quadrangle with a sunken courtyard separating it from the chapel. The dining room’s interiors carry the sunken brick paved floor inside and up a broad brick fireplace.

Student accommodation is neatly arranged in long rows. Each row is linked by cross beams, forming a journey through intimate courtyards and hinting at the broader farm landscape. The design always considered the possibility of addition – with potential for adding accommodation achievable.

The structural design concept was limited to bricks, concrete, timber, glass and tiles. All buildings are roofed with unglazed terracotta marseilles tiles that were chosen for their harmonious blending with the landscape and remaining building materials.

Designed before the sustainability concepts we know today – Alexander College was an intuitive response to concerns about the environment. Through a passive design approach, the college minimised energy consumption. The building was cited for climatic benefit, it was naturally ventilated and had its own water supply and sewage system.

Deep eaves protect the windows and thick masonry walls provide thermal mass. Using local materials and labour ensured transportation was minimal and the carbon foot print of the college’s construction was small.