COX VOX: The Healing Power of Place

COX ardently subscribes to the notion of “architecture as a healing art, not just as a beautification art”, a quote by late American Architect, James Polshek. As design leaders, our work in the sector creates spaces and places for healing, celebration and care underpinned by opportunities for wellness & prevention, trauma informed design, gender sensitive environments and sensorial stimuli considerations.

Informed by decades of significant public projects – from stadia to train stations, conference centres to airports –the everyday human experience is central to COX thinking when it comes to healthcare design.

We sat down with COX Directors Adam Hannon and Zoë King from Adelaide, and Patrick Ness and Paul Curry based in Melbourne, to explore their thoughts on healthcare design.

[above]: The New Footscray Hospital, designed by COX and Billard Leece Partnership

How is COX looking at health architecture through a new lens?

Paul: What’s interesting for us is the role of health buildings and precincts as major public infrastructure. How we make great places for people and how the links between healthcare and our day-to-day lives can improve the overall sense of community and wellbeing. An example is the new Footscray Hospital, where the entire community will be able to enjoy it as a public place and part of their daily lives – not just when they’re unwell.

Patrick: Hospitals are potentially some of the most important public buildings we could possibly be involved in. The reason being that when people are at their most vulnerable – and that includes births, deaths and everything in between – that’s the point at which the level of care we provide for people tells society much about where we are as a community. That is the lens we bring.

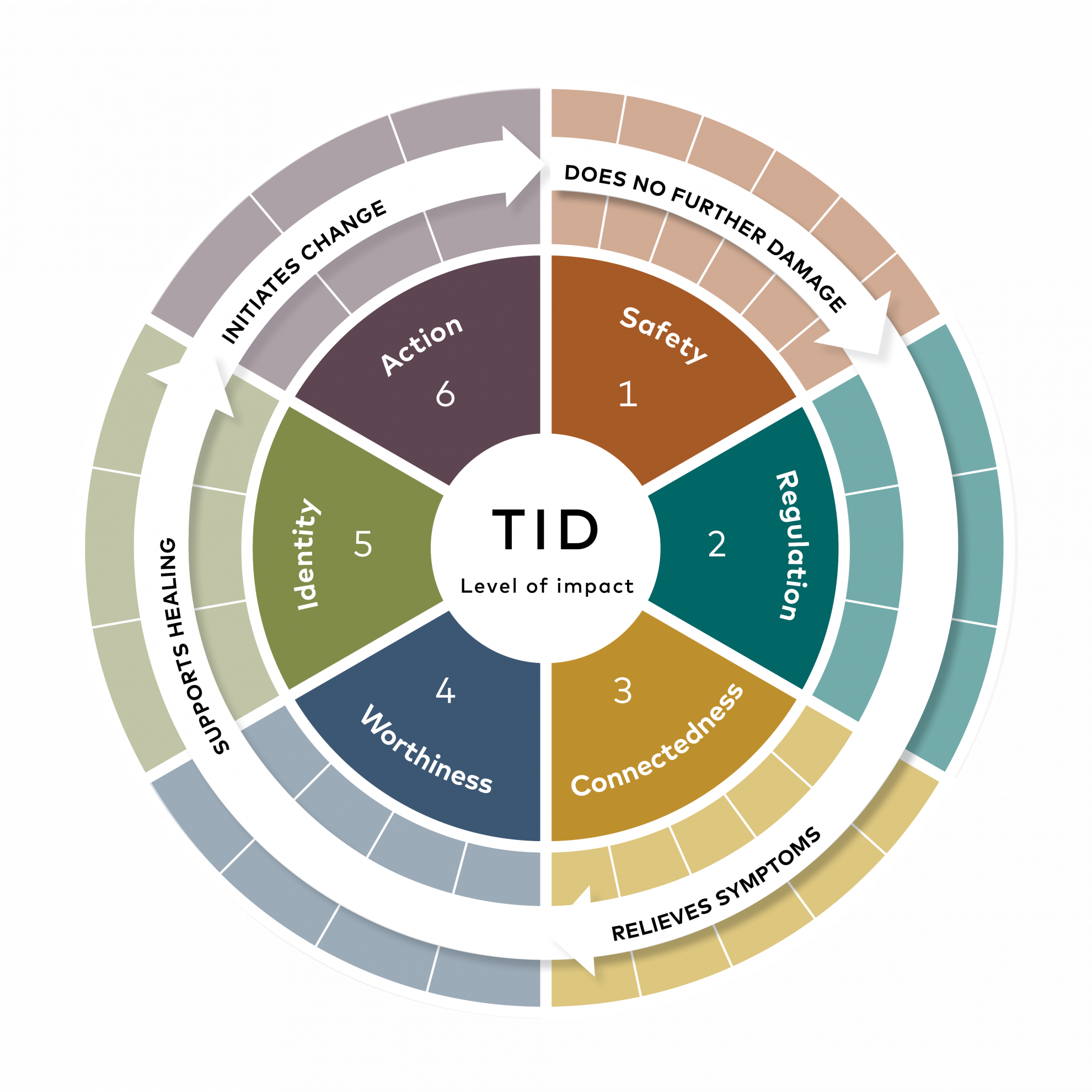

Zoe: Recently, we’ve been incorporating emerging research in trauma-informed design into our work, applying six key principles across various projects, including our award-winning Adelaide Studio. These principles aim to: provide physical and psychological safety, support nervous system regulation, mediate social connectedness, imply worthiness of dignity and beauty, encourage identity restoration and integration, and enable individual and community action. In high-needs environments like hospitals, we recognise that the physical space plays a crucial role in reducing re-traumatisation and fostering positive health outcomes, guiding our design approach to promote healing and wellbeing.

Below: Trauma Informed Design Principles Diagram

What do you want the community to feel when they come to a COX-designed building?

Adam: Every COX-designed project seeks to enhance public life. Whether it’s a hospital, school, workplace, or sports venue, thoughtful design can reduce stress, support wellbeing, and create spaces that feel intuitive and welcoming. You can see this in our hospital projects like Footscray Hospital and Perth Children’s Hospital, but just as much in Adelaide Botanic High School, where learning spaces inspire and support diverse students, or Karen Rolton Oval, where sport and community come together in the heart of Adelaide’s parklands.

Patrick: While COX has health expertise, we also embed aspects of other public work into hospital design. Having said that, the key feeling needs to be one of care, empathy, respect and that you are in a place of excellence. And the hospital should extend an invitation to participate to all aspects of the community in all circumstances. The feeling of being welcomed.

Paul: Our overall experience of hospitals can vary greatly, whether in care or recovery, and can be at extreme opposite ends. At one end you’ve got celebrations such as births and at the other, you’ve got sickness. And quite often the experience of hospitals – even the better ones – isn’t pleasant. We want to improve this for everyone; that human feeling that we have as we experience a space, beyond it being purely functionally driven.

What are design aspects that you feel are vital to people-centric architecture?

Patrick: At the new Footscray Hospital, the entire precinct surrounds a central green space. This will become the living, breathing heart to the hospital for staff, patients, families and the wider community. It will also support a positive arrival experience – whether coming to emergency or arriving by the front door, the central green space is designed to reduce stress through clarity of movement and spatial perception. Knowing where you are and where you can go.

This is combined with natural daylight, views of nature, art and greenery throughout treatment rooms, wards, nurse’s stations and common areas to create a sense of calm and reduce stress for patients as well as staff, families and other visitors.

Paul: The idea of designing for ease for everyone is so important – having intuitive movement flows, knowing where you’re going, having connections to the outside and the surrounding context and knowing the time of day are all important.

Zoe: A fundamental part of people-centric healthcare design is ensuring that patients feel connected—to their surroundings, to nature, and to a sense of normalcy. When someone is unwell, they shouldn’t feel cut off from the world. Natural materials like timber and stone help bridge this gap, bringing warmth and familiarity. Equally important is giving patients control over their environment. The ability to adjust lighting and temperature can significantly reduce stress, creating a sense of ease and comfort. Thoughtful material choices can also soften noise and introduce calming, familiar scents, shaping an atmosphere that feels less clinical and more restorative.

What does great design mean to you on a personal level?

Patrick: For me, the role of architecture is to ‘just make it a bit better’. When we act and bring our design skills to bear, we need to make it better and not simply aesthetically, but better in the full sense of this, for people. When people are at their most vulnerable is perhaps when we can help the most.

Adam: I’m deeply invested in creating spaces that not only define the urban landscape but also enhance the way people experience the world around them. Beautiful design is important, but great design goes beyond that. It’s about what we call ‘design excellence’ – creating environments that bring people together, support wellbeing, and leaving a lasting, positive impact.

Paul: I personally have a great love for large, complex public projects that improve their communities and their context. Through the design, the journeys that we go through, the challenges and delights are what make it enjoyable, particularly when we’re able to walk through and experience the project with the community. Being able to deliver something that is truly different and that will be there for the next 50 years is such an amazing opportunity.